“At this time I’d like to say a few words especially to my sisters: SISTERS. BLACK PEOPLE WILL NEVER BE FREE UNLESS BLACK WOMEN PARTICIPATE IN EVERY ASPECT OF OUR STRUGGLE, ON EVERY LEVEL OF OUR STRUGGLE.”

Assata Shakur

Women’s Right’s & Civil Rights

The Civil Rights movement was a complex social movement involving many different campaigns and nonviolent tactics. It is one of the longest and most impactful social movements led by African Americans and other Americans willing to challenge institutional racism. Traditionally, the image of the Civil Rights Movement is heavily concentrated on the glory and triumphs of Black men, while Black women are historical souvenirs. Black women’s sacrifice to the larger goal of civil rights for all Black people was either overlooked or misconstrued. The attitudes of Black women changed considerably throughout the Civil Rights Movement as pioneers of successful nonviolent demonstrations. The hypervisibility of Black women in the public sphere increased through the vast communication network from organizers to their community. Interpersonal community relationships were integral to mobilization efficiency in forming mutual aid systems. Social programs that provided food and education stimulated local communities, strengthening the capability of a grassroots movement. Motivated by varying religious, economic, or political interests, thousands of women nationwide joined the frontlines of the movement.

Activists in southern states faced immense social intimidation in public spaces from white nationalists and supremacists eager to perform nationalistic rituals. Black women used their hypervisibility as an advantage by using their learned trades and education to highlight institutional harm and practical execution of justice. In the public eye, Black women in leadership were presented as emasculating forces to men for voicing their opinions and expanding their rights. The patriarchal roots of American society valued Black women as biological work machines of the working class while uniquely imposing gender discrimination. A core part of racism is phenotypic, so women were judged by unfair beauty standards, which reflects how patriarchal violence was a tool of Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement.

Formerly and presently, Black women are the primary victims of domestic violence. Women’s autonomy became contingent on their compliance with traditional gender identity and proximity to men. Women practiced rebellion through noncooperation, refusing to be consumers or laborers in a society prioritizing “Separate but equal.” The increased literacy, voter registration, and legal victories during the movement ignored the invisibility of resistance to gender and racial oppression. Black feminists in the Civil Rights Movement undoubtedly were praised as leaders but ultimately not respected as human beings. Aside from the expectation of white violence, Black women were “handicapped” by sexism and the expectation of respectability politics. Black women’s pursuit of social justice has always centered on women’s rights to vote, education, and personal freedom. Black feminism underwent radical changes as women struggled for rights as women and Black individuals.

To fully understand Black women’s contribution to the Civil Rights Movement, we should focus on what events led to the radicalization of Black feminists from the start to the end of the Civil Rights Movement. An essential cause of radicalization is the demonstrations and leadership tactics Black women introduced to the core community in the South. In the larger context of the Civil Rights Movement, gender cast an undesirable separation in the treatment of Black women due to the respectability of political role in organizing.

Leadership based on Direct Action

When we holistically look at the role of Black women in the Civil Rights Movement, the successful campaigns early in the movement are a culmination of historical strategizing and community inclusion. Direct action, justice, and the will of liberation were introduced during suffrage demonstrations of the 1920s as thousands of Black women participated in marches. The goal of Black feminists in the suffrage movement was to garner voting rights as a marginalized community, which exposed a more significant issue of gender and race in activism. The 19th Amendment addressed the humanity and demands of white women, while Black women were disenfranchised due to the racial segregation of Jim Crow. Ideologically, there was a stark binary between the practices of white feminist Black feminists, yet there was a common denominator under the system of patriarchy and white supremacy. On a socio-economic and political scale, women were excluded from jobs, education, housing, and personhood. As we learn later in the movement from Coretta Scott King, the purposeful restriction of access to human needs is a form of violence. In American society, violence is escalated by all institutions and systems that profit from oppressive labor and social constructs. Black women advocating for the right to vote was only part of the fight; economic boycotts were also organized to advocate for workers’ rights. In the private sphere, Black women were paid less due to both race and gender, relegating them to domestic work for white families. For little pay and long hours, Black women were overworked and undervalued in society. According to Trena Armstrong, “They were seen as victims of their ignorance, living in Black communities of crime and poverty with high levels of premature pregnancies and other social infractions” (Armstrong, 2012).

Black women faced unique forms of sexism that impeded them from progressing in many fields and sectors of education and employment. Black feminists understood that they were not inferior and that the system could be changed through the power of the community. Black women wanted to send a message that their value was worth more than domestic servitude, and they would obtain freedom at any cost. As an integral part of the community, women organized speeches and demonstrations and formed clubs that could disseminate important information and offer opportunities to young women. Educator Nannie Helen Burroughs pioneered nonviolent resistance as the founder of the National Association of Wage Earners with Bethune Cookman. A core part of early Black feminism is the steadfast commitment to education, instilling consciousness and discipline into the next age of suffragists. Nannie opened the National Trade School for Women and Girls with the funds she raised plus savings to help hundreds of women in their academic success and personal development and further the fight for labor equality. The goal of Black feminists was to take the ugliness of struggle and transform it into equality, whether in theory or reality.

Radical World,Framework and Self

Across the vast contributions and theoretical frameworks of Black feminism, the word radical is not typically associated with the earlier eras. Mass-scale demonstrations by Black women were impossible to ignore since most if not all, Black women belonged to a national association or church congregation. There was power in numbers for a disproportionately marginalized group such as Black women, an advantage since they were highly educated, vocal, and active. Black women in leadership positions leveraged their platforms to constantly bring awareness to the violence the most vulnerable Black communities faced. Outspoken leader, Ida B. Wells’ strategic use of literature, does not fit the radical description since the critique and action of resisting violence is a natural response to being oppressed. She confronted the brutality and societal shortcomings of lynching against African Americans, producing thought-provoking works that highlighted the victims of these senseless acts. Ida’s proximity to violence shaped her fight for justice just as being a woman in a male-dominated world did. Ida collected her flowers during her lifetime since she refused to be defined by racial or gender barriers, a pressure all Black women in leadership faced to achieve their goals. The stigma of being the “First Black Woman” to achieve something opens up Black women to unsupported claims and attacks on multiple aspects of their identity. Ida was praised for her work in racial justice but failed to satisfy the societal boxes women were to fulfill early in their lives. Ida conditioned herself to a life of independence to a degree most Black women did not have at the time, decentering individuality.

In Jim Crow, racial expectations were reinforced to subjugate Black people, as Ida chronicled, but the patriarchy expected women to fall in line, especially Black women. Ida embraced the change while bigots discredited her woman since “She had “nerve” when expected to show empathy, she was “smart” when women were supposed to be subservient, and she had “no sympathy with humbug” when women were expected to be welcoming and accepting” (Clark, 2014).

This type of policing of Black women’s bodies would be a conversation that broke headlines decades after Well’s death. Wells embodied everything Black women socially critiqued about the vexing nature of sexism. Women were underestimated as leaders to strengthen the power status of men’s leadership roles. Black women’s operational leadership challenged conservative male leadership need to be prioritized. Male leaders were idealized public figures whose problems everyone seemingly resonated with and responded to. Organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee are well known for the work of men like King and John Lewis, a point made by Ella Baker. Ella developed the blueprint for demonstration and the founding of the SNCC. She introduced a decentralized approach to mobilization that focused on the self-sufficiency of any student to become a leader. Ella consistently voiced her dissatisfaction with the rigid mindsets about the appropriate gender of a leader and who can be considered one. At the beginning of 1960, she had already gained 20 years of civil rights experience, which she used to empower the next generation of activists. In comparing Ida B. Wells to Ella Baker, the definition of radical fluctuates between its adjective and noun properties.

1954 through 1960 is a historical period that incrementally changed the fabric of Black women’s narrative. As an activist, Ella Baker’s constructive guidance in pursuing independence instilled a strong sense of collectivism in protesters. The respectability of the movement did not match Ella’s radical views, “You didn’t see me on television; you didn’t see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come. My theory is, strong people do not need strong leaders.” Respectively, she embraced the type of freedom as Wells, even publicly disagreeing with some of the most famous male figures of her time. Radicalization in the Civil Rights Movement stemmed from inattentive behaviors, inaction to support women’s initiatives, and delayed progress. Black Women had to rely on each other, choosing between a radical world, radical self, or radical framework. During the Civil Rights Movement, the radical world exists in the willingness of bridge leaders or everyday women to change their conditions using nontraditional methods proactively. These are denoted by the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which resulted in legal victory. The radical framework is associated with the political views and nonviolent action of frequent Freedom Riders, marchers, and “jail, no bail” front liners executed. The radical self can manifest in various forms as a person could believe in the fundamental principles of the Civil Rights Movement but not necessarily women’s rights. Entering the ’60s, Black women’s survival and erasure intensified as the efforts grew more aggressive and, thus, more radical.

No Woman Left Behind

Camaraderie is an appropriate term to describe the leadership structure among women of the Civil Rights Movement. The shared goal of liberation attracted young activists to the cause since violence for Black children had no age limit. Children, teens, and young adults were crucial and active participants since these girls and women endured suffering at such young ages. Black women were fighting to survive gender-based violence and racial intimidation, one that the dominant culture in America had no interest in solving. Assault historically has been used to dehumanize and sexualize Black women without justice for the victims. Early organization for the Civil Rights Movement is inherently a women’s rights issue that demanded gendered violence be eradicated.

Under Jim Crow, Black women would never be adequately protected, which is why direct action was organized, such as the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor. Many Black activists advocated on behalf of 24-year-old Recy Taylor, who was brutally assaulted by four white men in 1944. As Ida B. Wells pointed out about violence against Black people, the government in both cases failed to prosecute or provide any legal resolve. Recy Taylor did not face intimidation alone, as she had the advocacy of some of the greatest Black minds on her side. Famously W.E.B DuBois and Mary Church Terrell ensured this reached national audiences as Rosa Parks used her own experiences with sexual assault to invoke conversation about violence against Black women. For Black women, sexual assault was a nonfactor under Jim Crow. It could coercively be used to subjugate women and falsely imprison men. Women were placed in a dangerous predicament in the private sphere of society since there was virtually no protection from spousal or external conflict.

Black women mobilized themselves in response to the overly masculine and demanding needs of the Civil Rights movement. The patriarchal values of the movement pushed Black women into the shadows while their male counterparts reaped the benefits of their labor. In a movement, Black Women have sacrificed for oppressive attitudes towards women, which were justified for the greater good. The fight for women’s liberation is omitted from Rosa Parks’s story in favor of the coordinated Montgomery Bus Boycotts, which was new. The 1960s is where we would acknowledge more of women’s roles, but there is an invisible component of Black womanhood. Black women were the most active and vocal, but their contributions were not good enough for mainstream audiences.

Black women were tired of bearing the burdens of what Pauli Murray coined as “Jane Crow.” Black women who led demonstrations like sit-ins, boycotts, or marches were isolated as a reactionary response to the collective struggle against misogyny. While Pauli Murray set the legal groundwork for Board v. Brown of education, S/he expanded the conversation about discrimination on the basis of sex. In the determination of the movement to eradicate white supremacy, freedom of women was an equally important demand. For Pauli and other activists, Black women had to ask themselves what they wanted on the path to liberation. Similar to Rosa Parks, Pauli investigated the ways sexism was handled during the movement stating, “The Negro woman can no longer postpone or subordinate the fight against discrimination because of sex to the civil rights struggle but must carry on both fights simultaneously” (Murray, 1963). The radicalization of Black feminists is not one clearly categorized by excessive violence or exclusionary methodologies, instead offering a solution-based organizational structure.

Unsung Hero/Heroines

Black women formed a collective identity that compartmentalized voting rights, women’s rights, and class consciousness to recruit participants across the North and South. As the Civil Rights Movement emerged as a credible force, many Black people were hesitant to join a movement that could potentially aggravate racial violence and transgression. The invisibility of Black women within Black freedom movements lies in the willingness of the community and male counterparts to abide by respectability politics. In the spaces where Black women could gather, they were superseded by the perceived courage and intellectual prowess of male ministers who insisted women stay in their biblically traditional roles. Radicalization in the early fifties focused on deconstructing the rigid view about women in leadership. Intergenerational respectability politics were meant to give Black women a sense of pride by reinventing the image of Black people to broaden the ranks of the movement. Gender in respectability politics closed more doors for Black women than it opened throughout the gradual change in its functionality.

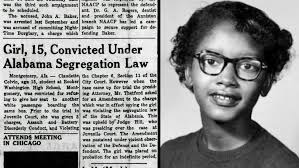

Black feminist causes for social justice were tainted by stereotypical portrayals of Black womanhood that sought to discredit the use of direct action. Disruptive actions such as sit-ins, marches, and strikes were used as early as 1940 by 30-year-old Pauli Murray and again by 15-year-old Claudette Covin in 1955. Both activists are left out of the conversation due to the demand for respectable identities representing the Civil Rights Movement. Though Claudette was only 15 when the laws of Jim Crow penalized her for disobeying, it was her pregnancy that ruffled the feathers of the Civil Rights Movement. Colvin’s “cry for justice” sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, though an older and more experienced Rosa Parks receives much of that credit. Rosa supported Claudette since the jailing of young African American children was far too familiar a practice when they demanded equality. Claudette and Rosa’s direct nonviolent action highlighted the intersection of the criminal justice system and how it adversely affected young women. To Claudette, “history kept me stuck to my seat. I felt the hand of Harriet Tubman pushing me down on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth pushing down on the other” (Metzger, 2021). Her activism was inspired by the collective justice efforts of Black women before her and the women whom society attempted to silence after her.

Black feminists wore many hats as the “bridge leaders” of the Civil Rights Movement, challenging the concept of leadership. Women often held lower-ranked positions in organizations that were male-dominated because “It was not that women could not be viewed as possessing leadership qualities; such qualities were viewed in positive terms within the community. Rather, it was that these qualities were suitable for local activities and committee duties” (Robnett, 1996). Striking respectability politics further subjugated women to these roles since other women chastized Bridge leaders who were vocal about gender exclusion. Discrimination based on sex proved to be a severe threat to the grassroots ideologies and practices of feminists.

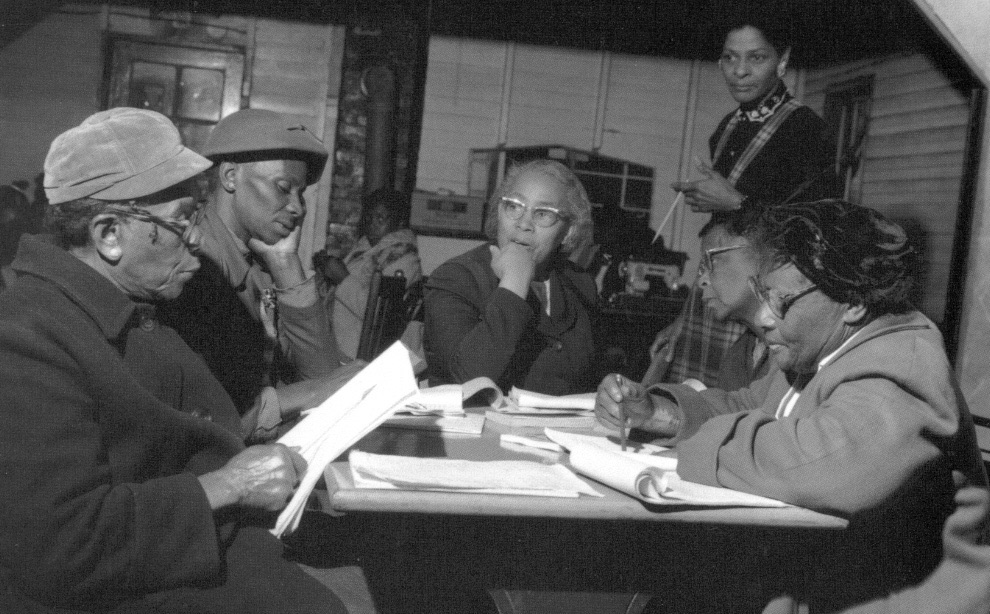

In women-centered organizations such as the Women’s Political Council (WPC) and The National Council of Negro Women, women used all forms of grassroots tactics to inform communities of the movement. There was a significant focus on educating rural Southerners and other community members about what the movement could do for them. Notable women such as Jo Ann Robinson, Bernice Robinson, and Septima Clark transformed communication in the Civil Rights Movement. Leaflets were distributed by the thousands to members of the Black community, promising to center their needs if they joined the cause. Black women’s organizations were influential in spreading the message about boycotts and demonstrations because of their backgrounds as educators. Equipped with knowledge, “part of Septima Clark’s program was to teach the community to read and write. She felt that literacy was the only way to enlighten the rural masses about their citizenship rights, and the best way to do this was to become actively involved in the pupils’ lives” (Robnett, 1996). Many women we attribute as leaders during this period had personal relationships with each other, becoming friends and family in their struggles. Friendship, mentioned before as comradery, is a staple of understanding Black feminism and how Black women advocate for each other even if it puts them in harm’s way.

Childhood of Young Activists

Women’s participation in social justice was a dangerous task and commitment, personified in the four years leading up to the Civil Rights Act. Institutionalization and criminalization of nonviolent direct actions by Black women produced an increase in intimidation tactics from white supremacist groups. The Civil Rights Movement gained more momentum, with martyrs and victims, followed by brutal police beatings and citizen vigilantism. Pauli Murray set the legal precedent for Brown v. Board of Education, which made desegregation in public schools possible five years prior. Elizabeth Eckford, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Gloria Ray Kalmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals of the “Little Rock Nine” lives were forever changed by the decision and the documented hostility of their white peers. These young students were taunted at school, and in the privacy of their homes, white students of Central High School made sure their disdain was felt. Chucking rocks, bricks, or dynamite at the students even with the “protection” of federal marshals.

The fall of segregation and the start of integration threatened the status quo provided by Jim Crow; children like Ruby Bridges were exposed to boundless violence. As a 6-year-old, Ruby indirectly became a civil rights icon on November 14, 1960, when she was escorted into her integrated school with the looming threat of racial violence. Segregationists of the time gathered every day to hurl racial slurs at her for pursuing an education, “She only became frightened when she saw a woman holding a black baby doll in a coffin” (Michals, 2015). Black children are a marginalized group on their own, habitually targeted by the conditions of segregation. Black students would usher in the second generation of civil rights activists as Ella Baker worked with students who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee in 1960.

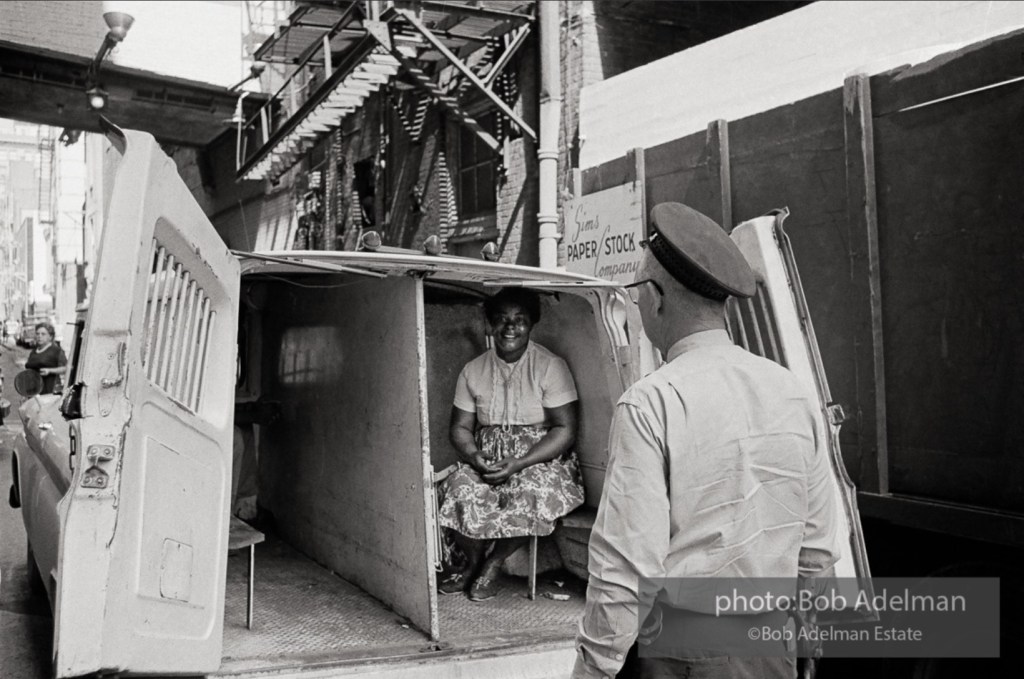

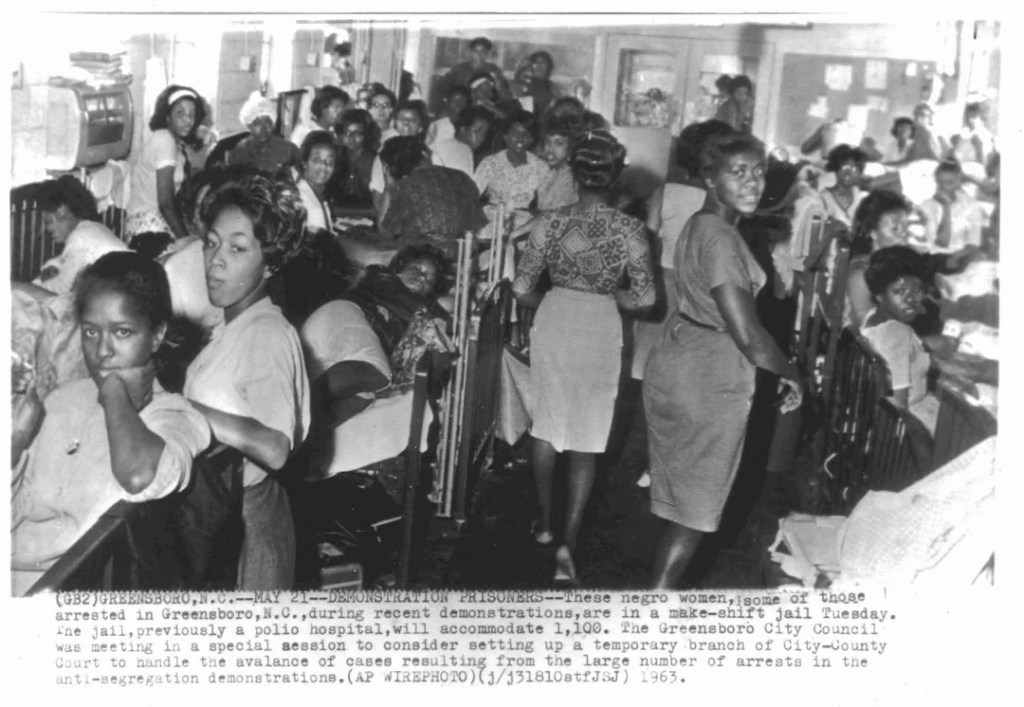

Diane Nash rose to prominence as a lead protest organizer and taught students to resist through nonviolent means. From North Carolina to Mississippi, Black girls, teens, and young adults were rounded up and placed in jail. Young Black women were familiar with racial discrimination even as children, which led to radical frontline inclusion. Students were tired of the older generations’ response to fighting Jim Crow and opted for hardline stances in their political ideology and practices. Students were disproportionately disadvantaged in their fight for voting rights from voter education co-option from larger Civil Rights Movement organizations. Parents of Black children tried their best to protect their children from the ugly reality of Jim Crow; however, young activists were called to disrupt the systems of power. Black children were not spared from dehumanization, and the cost of civil rights came at the expense of freedom. Young Black women walked out of school straight into the county jails, some the same age as Ruby Bridges and others at least 12-14 years old. As more “radical” demonstrations were organized by SNCC facing beatings at counters, the Children’s March in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 highlighted state violence. Police officers arrested children in the dozens until the police van was filled with the youngest civil rights leaders. The Leesburg Stockade happened one month before the tragedy of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing.

Daisy Bates to NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins, December 17, 1957. Typed letter. Page 2. NAACP Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (103.00.00) Courtesy of the NAACP //www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-rights-act/images/cr0103p1_enlarge.jpg

In August of 1963, over 30 young Black women were arrested and detained in an old prison named Leesburg Stockade. The constitutional rights and human rights of these young girls were violated as they were kept in unsanitary conditions for an unknown period of time. Some girls spent weeks in prison, keeping their spirits up through freedom songs and prayer. These young girls were mistreated daily inside the jail while those outside were being clubbed, hosed, and attacked by dogs. A then fourteen-year-old Juanita Freeman recalls, “That took the fear out of you. I think everyone who went to jail was willing to die” (Schwartz, 2018). Fear, as Juanita describes, was a tool used by Jim Crow, but jailing as a reaction to social justice was no longer a severe repercussion. After the conclusion of the March on Washington, women were disillusioned by the lackluster response to the proliferation of violence against Black girls. The explosion that killed Carole Robertson,14; Denise McNair, 11; Addie Mae Collins, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14, was the result of a targeted attack by KKK leader Robert Chambliss. Alabama was a hotspot for demonstrations as one of the most segregated states in the nation; Birmingham specifically was known for bombings.

Gender Discrimination and Inequality

Young African American women at the March on Washington, 1963. Photograph: Courtesy of the Bob Adelman Estate

Throughout the gendered context and defining periods of the Civil Rights Movement, the radicalization of women’s movements was evoked by the invisibility of labor inequality. The intellectual consciousness Black feminists embraced argued that social justice could not be reached if patriarchal systems were not deconstructed. The March on Washington centered on the male leadership of Martin Luther King, A. Philip Randolph, and Bayard Rustin, which frustrated the women who ensured the success of their committees. Pauli Murray directly asked Black women to center themselves since their male counterparts consciously infantilized them, despite undeniable success in the movement at the hands of women.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is frequently quoted for the famous “I Have a Dream” speech, yet women activists were once again slighted. Anna Arnold Hedgeman, who recruited over 40,000 demonstrators to the march, was unsettled by the exclusion of women from the speaking platform. The problem was that the lack of representation of Black women did not bother men like Bayard Rustin. Anna addressed this in a final organizing meeting before the march, “In light of the role of Negro women in the struggle for freedom and especially in light of the extra burden they have carried because of the castration of our Negro man in this culture, it is incredible that no woman should appear as a speaker at the historic March on Washington Meeting at the Lincoln Memorial” (Weaver, 2024 ). Erasing the physical work Black women achieved as bridge leaders undermines the abuse Fannie Lou Hamer suffered in 1963 Mississippi. Hamer, during this time, fearlessly joined the SNCC and advocated for voting programs despite being older and newly disabled from racial violence. To Anna and Fannie, including women was about more than being the head of an organization.

Women performed the same organizing tasks as men, spending countless hours traveling from state to state and hosting voter education workshops. It was not surprising Josephine Baker and Daisy Bates’ presence were forgotten as speakers, while Anna’s recommended speaker, Myrlie Evers, did not make it due to travel complications. Gender roles erased the strategic steps Black women took by asking them to embrace male dominance. Sexist ideas set a precedent that did not account for how all oppressive structures affected Black Women. In response to hostile environments, Black women combined their own cultural and intellectual identities in a form of feminism that acknowledged both the individual and community.

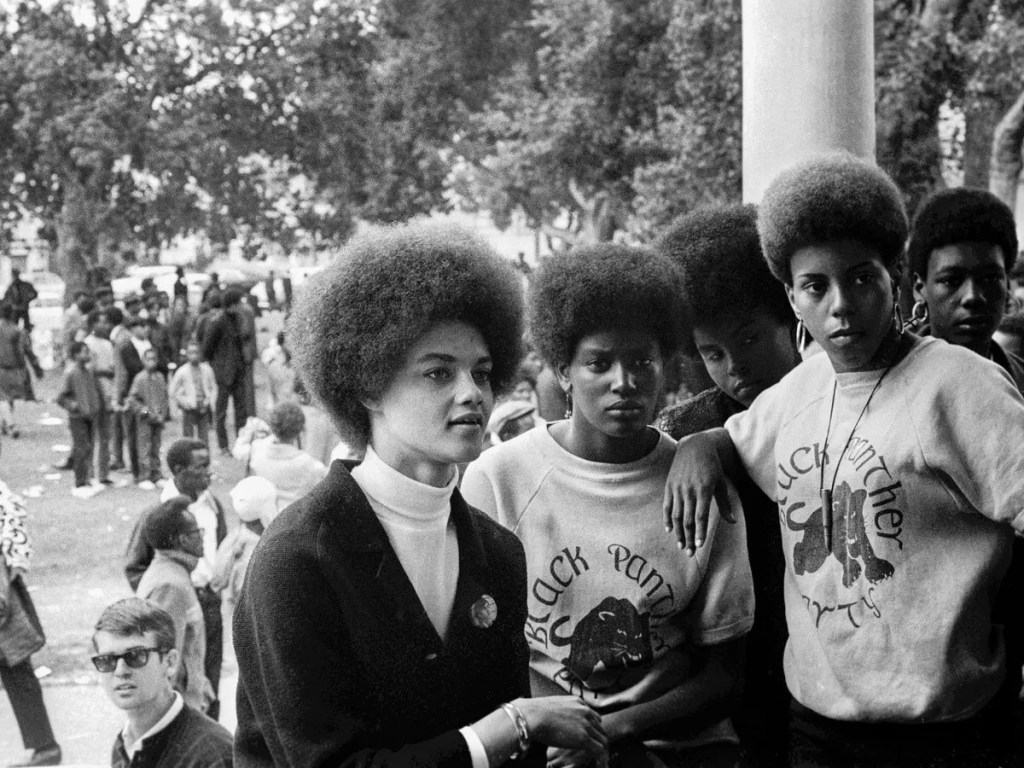

Kathleen Cleaver (left) communications secretary and the first female member of the party’s central committee, with Black Panthers from Los Angeles at the Free Huey rally in West Oakland, 28 July 1968.

The last push towards radical Black feminism started in 1966 when more women joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. However, many nonviolent campaigns characterized the Civil Rights Movement. Members of the SNCC did not feel as though the older generations’ movement addressed the significant concerns of violence Black people faced. In the times of Ida B. Wells, they advised African Americans to familiarize themselves with weapons in defense against racial terrorism. From 1892 to 1966, KKK violence and police brutality did not decrease, which angered militant minds of a younger Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement, as stated earlier, did not immediately appeal to all Black audiences due to fear of retaliation, even though there was mention of violence. Nonviolence was a hard selling point for some Black people since white supremacists and segregationists were not shy to commit domestic terrorism. Eventually, through enough demonstrations, nonviolence was able to be replicated on large and small scales. As the SNCC director, Ella Baker ensured all leaders practiced handling mobilization, advising against the standard hierarchical system. A turning point in the evolution of SNCC was reliance on top-down leadership, which led to women having “their experiences decontextualized with little regard to social realities of race and gender” (Mowatt, 2013).

The second generation of Black feminists, such as Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, and Ericka Huggins, embraced a more natural state of challenging respectability culture. Women of the Black Panther Party were fierce advocates for the international and domestic liberation of the African Diaspora. Militant behavior from women was unseen in the early days of the movement, but Black women of the BPP wanted to be more than trophy homemakers. Feminism during this time was still attached to the contextual framework created by white women, making it hard for Black women to describe themselves as feminists initially. This shift resulted from the harsh realities and message presented by the Black Panther’s implementation of community programs that the United States government undermined. Women were empowered by their Blackness, budding intellectual theories, and willingness to transform the BPP space. Though the Black Panther Party was primarily composed of women by the end of its tenure, it faced the same lack of representation as the Civil Rights Movement. Black women were able to combat misogynoir within the movement from the Eldrige Cleaver conflict and the larger context of the world.

Radical Reflection

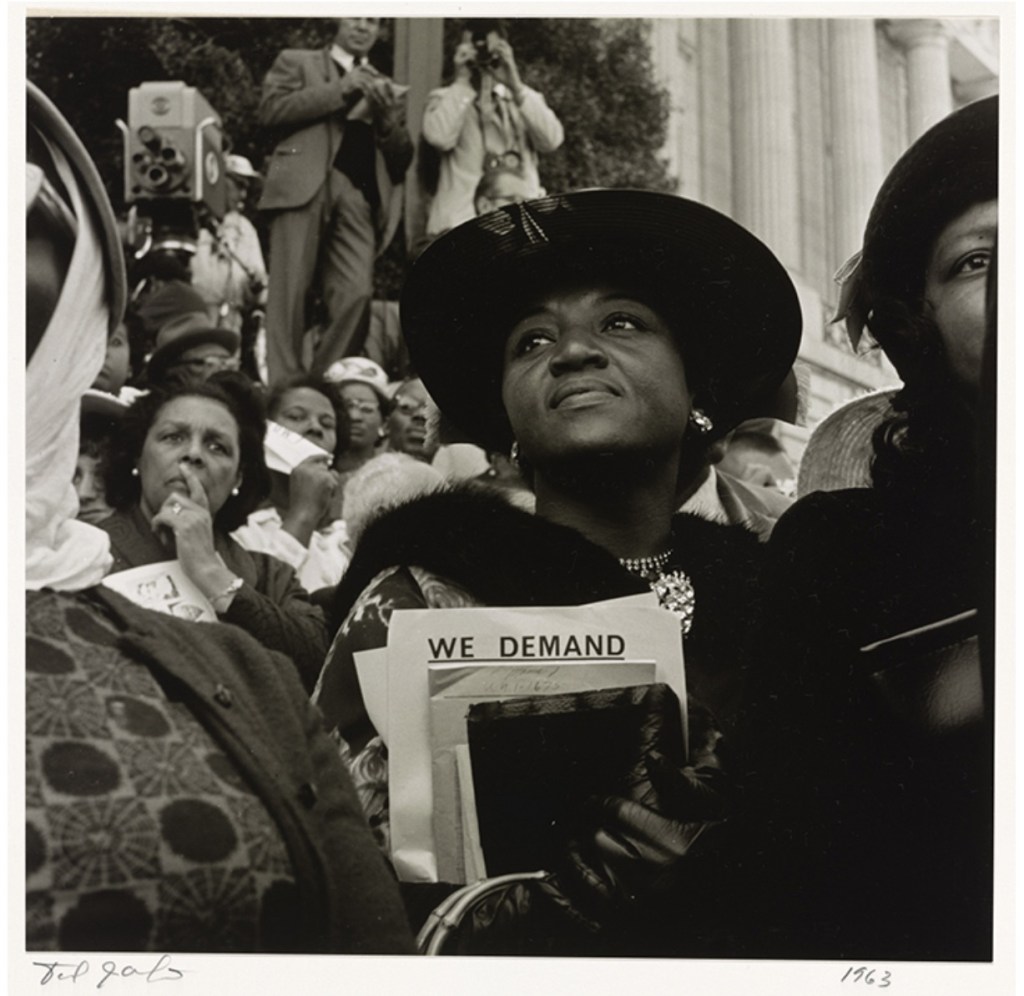

David Johnson. We Demand. 1963. Gelatin silver print. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (265.01.00) © David Johnson //www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.33810/

Black women underwent radical changes in philosophy through the intimate gender inequality faced within the Black community. Radicalization in the context of Black women’s leadership can be described as a rejection of power structures that did not benefit women or the whole of African Americans during the Civil Rights Movement. In a battle against Jim Crow in the South, Black feminists were disenfranchised through rigid labor roles, violence, and sexism from male counterparts. Over the 14 years of the movement, Black women built an inclusive network among themselves and other marginalized members of the Black community. This network was reliant on fulfilling the individual needs of participants while organizing toward a society where Black people determined their destinies. The concerted efforts of Black women from 1954 to 1960 ensured that the general population was prepared for mass mobilization while also providing wellness and resources. Black women were heavily involved in the movement and consistently spoke out against how the Civil Rights Movement had done little to represent the voices and work of women equally. Respectability politics is an underlying barrier to women’s leadership and treatment in the movement from both men and women. At the beginning of the Civil Rights movement, it was a tool of demonstration etiquette that was utilized to police the bodies of Black women. In the 50’s and 60, the actions taken by Black feminists were considered radical, though most of the actions were campaigns to help poor and uneducated Black people understand their constitutional rights. Black women were radicalized by the imprisoning and murder of Black girls who are nameless and mourned.