Introduction

The women’s suffragist movement in America broke many barriers for white women, while complacently building them for black women. Both groups of women worked together for the common goal of gaining voting rights, however white suffragist made it clear marginalized voices and issues were indifferent to their objective. Though not all white suffragist ostracized black women from the movement, their support surfaced some of the first examples of performative activism. Various suffrage groups were formed statewide with the purpose of mass organizing women through marches, picketing and conventions. These groups consciously prohibited membership for black women, limiting visibility of the fight against racism and sexism. Separation by race in the suffrage movement forced black women to create their own group, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, gaining support from over 40,000 black women.

Same fight, different outcomes

In the 1875 Supreme Court case Minor v. Happersett, suffragist focused their attention on creating a new suffrage amendment or state led voting. After Virginia Minor illegally registered to vote in an upcoming election under the argument that the Fourteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote because they were citizens. This tactic of illegal registering and attempts to vote were not new to the movement, however Minor’s lawsuit was the first to make it to the court. The lower courts and the Missouri Supreme Court ruled against Minor until the case reached the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Morrison Waite issued the court’s ruling, which held, “No argument as to woman’s need of suffrage can be considered. We can only act upon her rights as they exist. It is not for us to look at the hardship of withholding. Our duty is at an end if we find it is within the power of a State to withhold.” (Minor v. Happersett, 21 Wall. 162 (1875). After the ruling suffragist focused on changing the Constitution itself through carefully constructed language to support the document. 3 years later in 1878 Susan B. Anthony wrote the Woman Suffrage amendment, that failed to pass but provided the foundation of what would become the 19th amendment.

Many women were subsequently arrested and fined as punishment for breaking the law, as their black counterparts were lynched, assaulted or killed for the same crime. White suffragists were recognized as citizens perennially shifting the goalpost of “universal suffrage” in times of Reconstruction and Jim Crow. From 1878 to 1919 suffragist sustained the movement through civil disobedience, until gaining support from President Woodrow Wilson making voting equality for women a national cause. On, “June 4, 1919: The Senate adopts H.J.Res. 1 by a 56-to-25 vote, sending the constitutional amendment to the states for ratification.” (“Women’s Suffrage: Fact Sheet,” n.d.). Tennessee was the last state to finish the ratification process on August 18, 1920, 7 days later August 26,1920 the Nineteenth Amendment was passed. This amendment states that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” (“Nineteenth Amendment | Browse | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress,” n.d.). Although 3 million black women procured their right to vote, systemic racism remained an obstacle.

Systemic burden of Black voters

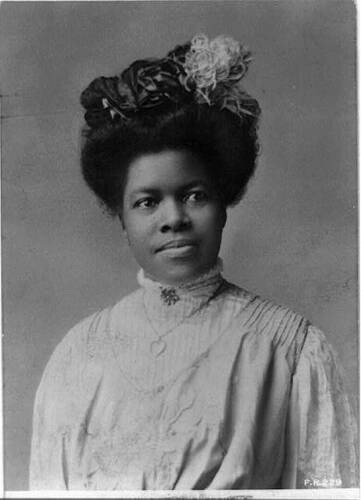

Throughout the period of Jim Crow African American voters faced intimidation, heightened racial violence and pseudoscientific ploys as the Civil Rights Movement mobilized the nation towards desegregation and equality. Jim Crow tools such as poll taxes, literacy tests, “grandfather clauses,” and “white primaries” (Costly 2019), posed as a strong deterrence in registering to vote. This calculated action served to undermine and disenfranchise black voters even if they were guaranteed the right. Nevertheless, black women continued to prevail under these strenuous circumstances. Women like Fannie Lou Hammer and Rosa Parks defied racial barriers by organizing marches to the polls and spreading knowledge of constitutional rights among the African American population resulting in the proliferation in voter registration. The monumental march in Selma, Alabama, showcased the brutality of seeking justice within the electoral process. Through decades of championing black women worked tirelessly to bring into fruition with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Under the Voting Rights Act discriminatory voting practices were banned stating, “No Voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on the account of race or color.” (“Voting Rights Act of 1965 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives,” n.d.). The impact of this act upon the federal system of American government is significant in a wider sense, for it may foreshadow a similar congressional approach to other civil rights abuses under the mantle of the fourteenth amendment. (“Voting Rights Act of 1965” 1966). In the modern era the 19th amendment has become synonymous with the names of Susan B. Anthony or Elizabeth Cady Stanton leaving out the Black women such as: Mary Talbert, Ida B. Wells Barnett, Mary Church Terrell and many nameless Black women who forged the path of suffrage. The Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed white suffragist the right to vote as black suffragists were overshadowed and advised to assist from a distance. Over the course of the century Black women remained adamant in their advocacy, dissemination of resources and will to challenge the status quo. The fight for true voter equality continues with the Black women of the 21st century, who have cultivated their own movements using lessons of the past.